One of the questions I had to answer for myself when my husband and I decided to plan the trip and buy tickets on the orchestra level, was why it was important for me to see the show in NYC, on Broadway, with as much of the original cast as possible. I am pretty sure that my desire comes from both a place of fandom as well as a theatre-maker. As a fan, being able to see the people responsible for the show in the flesh was beyond words. When Lin-Manuel Miranda walked out on stage, the entire theatre erupted in joy, myself included. We knew he was going to be on stage (the program tells you who is performing that night and no other announcements about understudies or swings was made), but it was still pure delight to actually see him. To know that he was going to spend the next 2.5 hours with us sharing his precious musical with us. Truly amazing. Of note, we were fortunate to have the entire original cast perform on Wednesday evening except for Jonathan Groff because he recently left the show and a new King George III (Rory O'Malley of Book of Mormon fame) had been brought in recently. There really aren't adequate words to explain how cool it is to see the people who you've been listening to for months as disembodied voices. It really is the most amazing thing.

In the podcast, they use the word "kinetic" to describe the show. This is a very apt way of explaining what is, for lack of a better term, missing when you listen to the cast album. I'll admit I don't have a ton of recording-to-live experiences to draw upon, but I'd wager Hamilton's particular staging and choreography are in fact very special. The soundtrack tells you the story, you get the wit, the brains, the allusions to musicals and hip-hop/rap styles, and the beautiful music and arrangements. But that's only a part of what makes up musical theatre. The choreography, the blocking, the interactions between characters, the space, the costumes, the lighting... that's what you don't get until you're sitting in the Richard Rodgers Theatre, in the room where it happens.

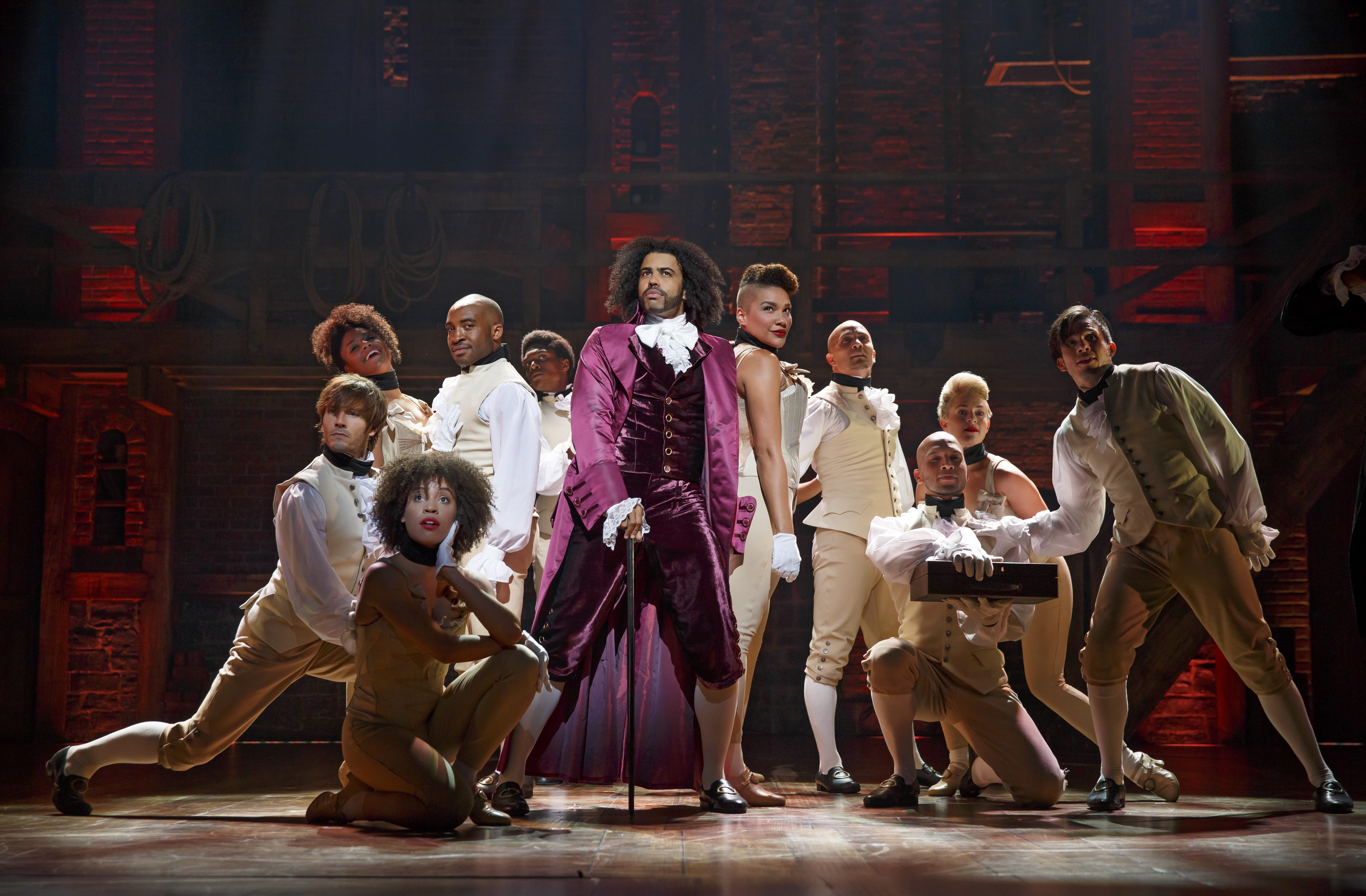

As a designer, in my opinion the creative team pretty much nailed it. I'd say that the set isn't super special, but it is perfect for the show. It isn't a revolutionary set design, it is form following function, and also pretty to look at. It will be interesting to see how it changes for the tour. While not necessary, the nested turn-tables play a large role in how the show is blocked and how the furniture, which makes each different scene, is moved to and from the wings. For that alone I'll want to see the national tour. However, since the pictures started to come out from The Public, I've had some issues with the costume design. Overall, again, it's a form following function thing. It's pretty, not flashy, it tells the story. The mixture of period costumes with natural hair has grown on me, but sometimes it feels like it falls a little short of being more of a workshop feel vs. a fully realized play. I don't know how I'd have done that part differently, but it is ... something that makes me pause in heaping praise on the costume design. The thing that bugs the crap out of me in regards to the costume design is the ensemble, specifically the women. They had two base costumes:

|

| one that mimicked the male ensemble, with waistcoats over their leggings and with boots |

|

| one that had them wearing corsets over their leggings, with high-heels |

I get it. It's a way to allow the women to be women in some scenes (crowd scenes, Thomas Jefferson's staff, etc) and still be able to dance. An when they are wearing just the waistcoats, they're soldiers. In this costume, gender is erased from the narrative the way that the casting erases race. Cool. Totally get it. HOWEVER, women in leggings and a corset is ... sexy? It feels more incomplete than the male costumes. It looks more like they are wearing underwear and the guys are all wearing clothes (notice how the men now have shirts on under their waistcoats and we're not seeing their muscle-y, dancer-arms?). It's a small thing. It's a nit-picky thing, but it's also the thing that really shows that the entire creative team is male. And, to be sure, we don't know that Paul Tazewell (costume designer) didn't try something different, but... the final product is allowing the male gaze into the conversation when, in other places, gender is neutralized. So, that's my one complaint that, even seeing the entirety of the costume vision, still remains.

And, I'm going to dedicate an entire paragraph to tell you how the lighting design was one of the best parts of the entire show. Musical lighting is an entirely different beast than doing design for a regular play. It lives in this place that straddles reality and rock show. And this lighting design does just that. The entire ceiling of the stage was solid black with lighting instruments. Usually musicals are pretty light-rig heavy. However, I've never been in a space where I've only seen lighting instruments. In part because many other musicals rely on things flying in and out. I think the only thing that flew in were lanterns. So the lighting designer got to use up the air for all kinds of moving lights, LEDs, specials... the works. And DAMN, he deserves to win the Tony, no questions asked. When describing the aim of lighting design, it is often described as "painting with light." Using light to evoke mood, place, time of day, and enhance the physical world is a tall order. For the most part, as a designer, you want your design to support the story but not be visible. Something the audience appreciates -- hey, I could see their faces or hey, that sunset on the back wall was pretty or hey, when Sweeney Todd slit their throats, the red lights helped heighten the drama -- but for the most part isn't really its own character in the story. And that's not because it can't be but because it's really, really hard. It's better to aim to be a supporting, unobtrusive character because if something goes wrong (the actor misses their cue/light or the cue is called in the wrong spot or, heaven-forefend, the instrument doesn't work) it won't be noticeable. And then there are shows on Broadway in which the lighting design is more rock show than just lighting their faces. Hamilton is one of those and so much more. The designer very much painted with light. During the songs where the hurricane in Hamilton's life is evoked: there was a hurricane on the stage floor. When Hamilton is walking when it's "quiet uptown" those same lights made cobblestones for him to walk on. When Hercules Mulligan jumps out in his solo song and when the Marquis de Lafayette sings his song and when Burr sings "The Room Where it Happened" the lights were bouncing all over the place and would give a Beyoncé show a run for its money. AND IT WAS PERFECT. Perfect. Not too much, not too little, but magical and a way to direct focus and enhance the story. If this was what I was told lighting could do before I started down the road as a scenic/costume designer, I'd have more seriously considered lighting design. That's how amazing the damn thing was. (AND, let's not forget, that the reason it worked was because the stage manager did an amazing job calling the show and the cast hit their mark, EVERY SINGLE TIME.)

Lastly? I have to speak to the ensemble nature of the show. Arguably, typical musical structure really exists as a star vehicle. There are solos for the main characters, supported by the ensemble, then they leave the stage, the story is advanced with some big, flashy ensemble numbers, and then the stars come back on and sing, etc etc. This show doesn't do that. From the cast album you know that Leslie Odom, Jr. as Burr sings most of the show as the narrator. That's unusual to have one person carry both the narration and an actual character story line so exclusively. Listen to the rest of the show. Renee Elise Goldberry as Angelica sings the beginning of "Quiet Uptown"... why? It's moving to have Angelica sing that song about her sister and brother-in-law, but it's not necessary as part of the story, really. You have a sense when you listen to it that there is an ensemble nature to the performances, but when you see the staging, you see how the director has characters not in the scenes pay witness by being on the balcony of the set and in the wings, watching. It's a small thing, and again, most lay audience members aren't really going to get it on a conscious level. But they're going to have a sense that the telling of the story belongs to everyone on stage. Especially with the picking out of ensemble members to play the small but important parts: Charles Lee, Sebring, and George Eaker (they guy who duels with Phillip Hamilton). Those are ensemble members who dance and sing their asses off THE ENTIRE SHOW and then KILL IT in these parts. This is all a part of the nod to the over-arching theme that LMM is playing with right in the middle of the show: "You have no say who lives who dies who tells your story." Or, in the opening song when the cast sings "We're waiting in the wings for you." The breakdown of the fourth wall is there, subtly, but there to remind us that we're not watching a period drama about our founding fathers, we're watching talented, diverse people of the twenty-first century celebrating the life of a man who we've nearly forgotten using the tools we have now.

The ensemble nature of the show is related to the little lines in the album that some people have nitpicked. Three examples: When Hamilton says "That's true" after the tidbit about how Martha Washington named her feral tom cat after him. When Jefferson says "Don't act surprised you guys 'cause I wrote 'em" after he references "Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" during "Cabinet Battle #1". And when Adams says "Which I Wrote" after Jefferson (?) mentions the Bill of Rights a scene or two later. They all feel a little weird when you're just listening to them out of context on the album. But when you see how they are delivered to the audience (in the case of the first one), to a cast member who is just off stage with no lines (the case of the line from Adams), and a combo of both (in the case of Jefferson), you see, I'd wager, the evolution of the show through being performed by living breathing, talented actors. I can't say (maybe it is clear in the book that just came out about the process of writing the show), but I'd say these are examples of how the final script is often created in workshop and performance because, hey, theatre is not just what's written on the page. Theatre is an alchemy of the collaboration of so many artists coming together to tell a story and that is what makes it special and important as an art form. And that, specifically, is how Hamilton has become the phenomenon it is. When you read the articles and statements from artists about Lin-Manuel Miranda, from the beginning of his career with In the Heights, the guy is generous and humble and welcomes people in to his process from beginning to end. And he's brilliant with words and music and form and everything.

In the podcast that I linked to above one of the people mentions that sometimes she gets annoyed with the overwhelming response to the show, how it has become such a huge, commodified cultural phenomenon that exceeds what most theatrical turning points (Rent, The Lion King, etc) have been granted by the world. It can be annoying, but then she reminds herself that it's giving power to people like LMM and Leslie Odom, Jr. and Daveed Diggs and Renee Elise Goldberry and and and for their next project. It's gilding them with praise and granting them a place in cultural history that transcends Broadway and theatre and will propel them, as amazing artists and, more importantly, generous souls to help change the world we live in. And that is what makes all of this so incredibly exciting to be a theatre-maker during the time of Hamilton.

And, I'm going to dedicate an entire paragraph to tell you how the lighting design was one of the best parts of the entire show. Musical lighting is an entirely different beast than doing design for a regular play. It lives in this place that straddles reality and rock show. And this lighting design does just that. The entire ceiling of the stage was solid black with lighting instruments. Usually musicals are pretty light-rig heavy. However, I've never been in a space where I've only seen lighting instruments. In part because many other musicals rely on things flying in and out. I think the only thing that flew in were lanterns. So the lighting designer got to use up the air for all kinds of moving lights, LEDs, specials... the works. And DAMN, he deserves to win the Tony, no questions asked. When describing the aim of lighting design, it is often described as "painting with light." Using light to evoke mood, place, time of day, and enhance the physical world is a tall order. For the most part, as a designer, you want your design to support the story but not be visible. Something the audience appreciates -- hey, I could see their faces or hey, that sunset on the back wall was pretty or hey, when Sweeney Todd slit their throats, the red lights helped heighten the drama -- but for the most part isn't really its own character in the story. And that's not because it can't be but because it's really, really hard. It's better to aim to be a supporting, unobtrusive character because if something goes wrong (the actor misses their cue/light or the cue is called in the wrong spot or, heaven-forefend, the instrument doesn't work) it won't be noticeable. And then there are shows on Broadway in which the lighting design is more rock show than just lighting their faces. Hamilton is one of those and so much more. The designer very much painted with light. During the songs where the hurricane in Hamilton's life is evoked: there was a hurricane on the stage floor. When Hamilton is walking when it's "quiet uptown" those same lights made cobblestones for him to walk on. When Hercules Mulligan jumps out in his solo song and when the Marquis de Lafayette sings his song and when Burr sings "The Room Where it Happened" the lights were bouncing all over the place and would give a Beyoncé show a run for its money. AND IT WAS PERFECT. Perfect. Not too much, not too little, but magical and a way to direct focus and enhance the story. If this was what I was told lighting could do before I started down the road as a scenic/costume designer, I'd have more seriously considered lighting design. That's how amazing the damn thing was. (AND, let's not forget, that the reason it worked was because the stage manager did an amazing job calling the show and the cast hit their mark, EVERY SINGLE TIME.)

Lastly? I have to speak to the ensemble nature of the show. Arguably, typical musical structure really exists as a star vehicle. There are solos for the main characters, supported by the ensemble, then they leave the stage, the story is advanced with some big, flashy ensemble numbers, and then the stars come back on and sing, etc etc. This show doesn't do that. From the cast album you know that Leslie Odom, Jr. as Burr sings most of the show as the narrator. That's unusual to have one person carry both the narration and an actual character story line so exclusively. Listen to the rest of the show. Renee Elise Goldberry as Angelica sings the beginning of "Quiet Uptown"... why? It's moving to have Angelica sing that song about her sister and brother-in-law, but it's not necessary as part of the story, really. You have a sense when you listen to it that there is an ensemble nature to the performances, but when you see the staging, you see how the director has characters not in the scenes pay witness by being on the balcony of the set and in the wings, watching. It's a small thing, and again, most lay audience members aren't really going to get it on a conscious level. But they're going to have a sense that the telling of the story belongs to everyone on stage. Especially with the picking out of ensemble members to play the small but important parts: Charles Lee, Sebring, and George Eaker (they guy who duels with Phillip Hamilton). Those are ensemble members who dance and sing their asses off THE ENTIRE SHOW and then KILL IT in these parts. This is all a part of the nod to the over-arching theme that LMM is playing with right in the middle of the show: "You have no say who lives who dies who tells your story." Or, in the opening song when the cast sings "We're waiting in the wings for you." The breakdown of the fourth wall is there, subtly, but there to remind us that we're not watching a period drama about our founding fathers, we're watching talented, diverse people of the twenty-first century celebrating the life of a man who we've nearly forgotten using the tools we have now.

The ensemble nature of the show is related to the little lines in the album that some people have nitpicked. Three examples: When Hamilton says "That's true" after the tidbit about how Martha Washington named her feral tom cat after him. When Jefferson says "Don't act surprised you guys 'cause I wrote 'em" after he references "Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" during "Cabinet Battle #1". And when Adams says "Which I Wrote" after Jefferson (?) mentions the Bill of Rights a scene or two later. They all feel a little weird when you're just listening to them out of context on the album. But when you see how they are delivered to the audience (in the case of the first one), to a cast member who is just off stage with no lines (the case of the line from Adams), and a combo of both (in the case of Jefferson), you see, I'd wager, the evolution of the show through being performed by living breathing, talented actors. I can't say (maybe it is clear in the book that just came out about the process of writing the show), but I'd say these are examples of how the final script is often created in workshop and performance because, hey, theatre is not just what's written on the page. Theatre is an alchemy of the collaboration of so many artists coming together to tell a story and that is what makes it special and important as an art form. And that, specifically, is how Hamilton has become the phenomenon it is. When you read the articles and statements from artists about Lin-Manuel Miranda, from the beginning of his career with In the Heights, the guy is generous and humble and welcomes people in to his process from beginning to end. And he's brilliant with words and music and form and everything.

In the podcast that I linked to above one of the people mentions that sometimes she gets annoyed with the overwhelming response to the show, how it has become such a huge, commodified cultural phenomenon that exceeds what most theatrical turning points (Rent, The Lion King, etc) have been granted by the world. It can be annoying, but then she reminds herself that it's giving power to people like LMM and Leslie Odom, Jr. and Daveed Diggs and Renee Elise Goldberry and and and for their next project. It's gilding them with praise and granting them a place in cultural history that transcends Broadway and theatre and will propel them, as amazing artists and, more importantly, generous souls to help change the world we live in. And that is what makes all of this so incredibly exciting to be a theatre-maker during the time of Hamilton.